As a trans Chinese-Canadian artist / activist / designer, I find language a very powerful force in my daily life. I am exploring different ways in which typography can illustrate certain aspects of our lives, either through unlearning or relearning it. What are the origin stories of the words we use daily? How does language govern the way we perceive ourselves? Who has the right to reimagine our futures?

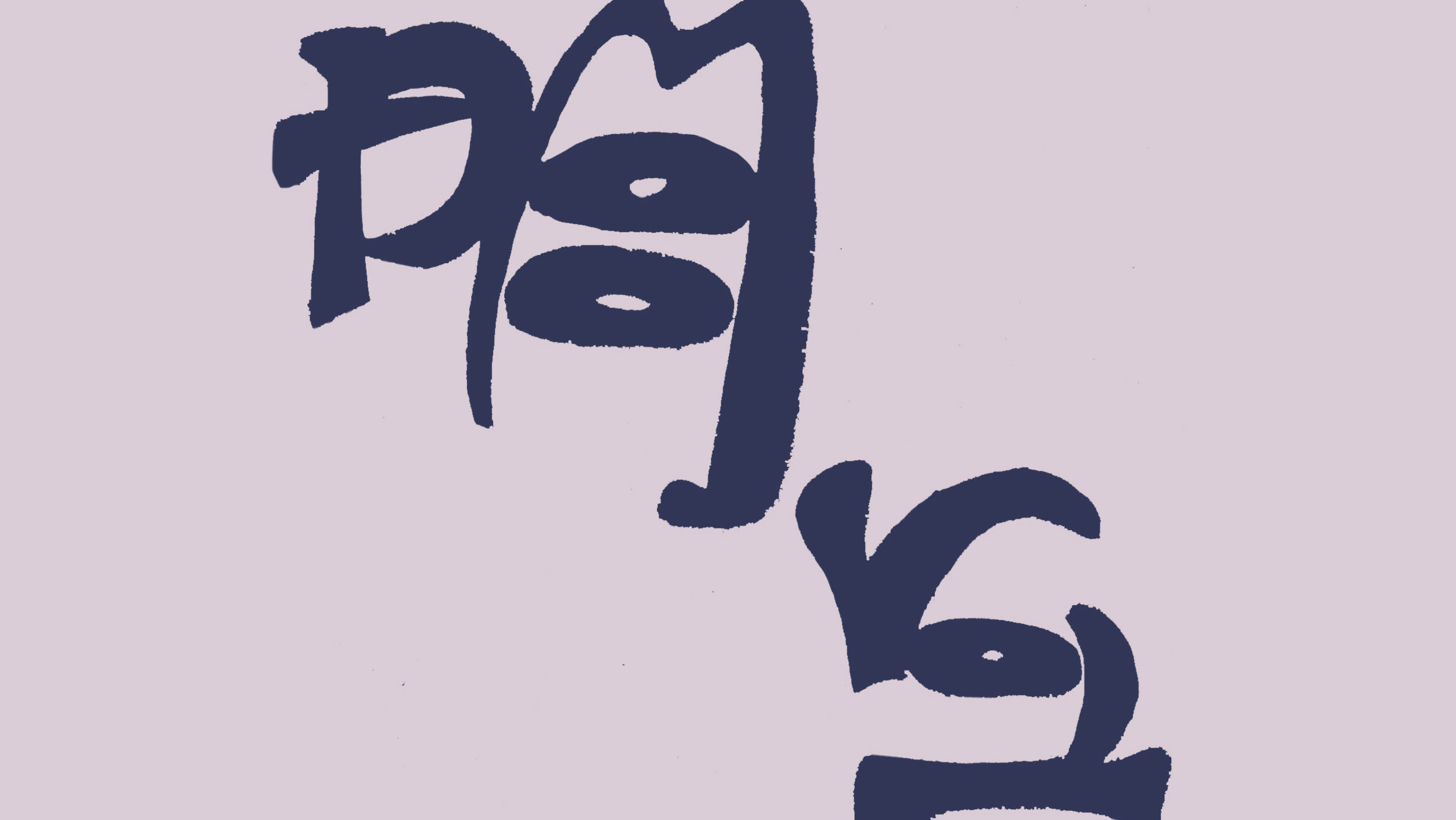

Through visual poetics and speculative typeface design, “Filling Gaps” resists against colonial uses of language, and asserts suppressed diasporic geographies, queer bodies, migrant histories, and diverse identities. It opens up a space for intergenerational, cross-geographical, cross-lingual discourse, which can be both disruptive and liberating. The world is changing constantly and so has language. These ideograms are a way of speculating on the politics and history behind language and queering the way we interact with our diasporic tongues.

This project consists of a collection of reimagined ideograms, which all have diverse visual forms, unique sounds, and tell a story of their creation. They are not bound to one singular interpretation/sound, they are vessels that you can fill your voices into. I will be compiling suggestions/submissions into an ongoing open typeface collection, and invite you to join this conversation about language x queer diaspora with me.

The character for medicine, 藥 (yào), is composed of two parts: The top radical, 艹, grass + The lower radical, 樂 (lè/yuè), meaning joy/happiness/music. Our ancestors believed that joy/music had the power to harmonize one’s soul in ways that traditional medicine could not.

The character 他 (tā), in much of Chinese history, served as a gender-neutral pronoun. 他 is composed of the left “human” radical: 人, 亻. The need to separate “he” and “she” was due to Western influence of the first women’s rights movement. The government, pressured by this burgeoning Western influence, thus created a new character 她, with the left “woman” radical: 女. To bring light to the changes in history to 他, the character 日也 was created. This character 日+也, uses 日, the sun radical. It is intended to identify any living organism underneath the sun, because after all, aren’t we all sun people.

氵人 (shén) is composed of the left radical, 氵, three drops of water + the right radical, 人, human. The sound of 氵人 is synonymous to 神 (shén), meaning spirit/soul/mind/heart/inclusive/community. Souls fly above clouds, crouch in rice paddies, and flow like water to dwell between spaces. 氵人 is fluid, amorphous, non-conforming, and open to possibility.

“Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.” - Bruce Lee

“Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.” - Bruce Lee

宀 身 (gēh) is composed of the top radical, 宀, roof, + the bottom radical, 身, body. It sounds like 家 (gēh), which means home in my native tongue Teochew. Queer bodies are erased, invisible, uncomfortable. The world tells us “you don’t belong here”, “you’re not good enough”, “you don’t look trans enough”. But we exist, this body is ours, this skin is malleable, our bodies are home.

“Loving one’s home is not about being fixed into a place, but rather it is about becoming part of a space where one has expanded one’s body, saturating the space with bodily matter: home as overflowing and flowing over.

Homes are effects of the histories of arrival. Diasporic spaces do not simply begin to take shape with the arrival of migrant bodies; it is more that we only notice the arrival of those who appear “out of place.” Those who are “in place” also must arrive; they must get “here,” but their arrival is more easily forgotten, or not even noticed.” - Sara Ahmed

“Loving one’s home is not about being fixed into a place, but rather it is about becoming part of a space where one has expanded one’s body, saturating the space with bodily matter: home as overflowing and flowing over.

Homes are effects of the histories of arrival. Diasporic spaces do not simply begin to take shape with the arrival of migrant bodies; it is more that we only notice the arrival of those who appear “out of place.” Those who are “in place” also must arrive; they must get “here,” but their arrival is more easily forgotten, or not even noticed.” - Sara Ahmed

愛变 (aì) represents trans4trans love, the most tender, the greatest love, I love you and we deserve the world. The top is the character love 愛 (aì) and the bottom is the character trans 变 (biàn; 变性人).

We are visible everyday. Visibility won’t serve us though, there are a lot more things to make sure that we are safe than just recognizing our existence. Continue learning and unlearning!

And there’s no one way of being trans, that just forces the binary. Some trans people choose to medically transition, and some don’t. Some trans people choose to legally change their names or ID documents, and some don’t. Some trans people choose to change their appearance (like their clothing or hair), and some don’t. Likewise, some trans people may want to do many of those things but are unable to because they can’t afford it or for safety reasons. A trans person’s identity does not depend on what things they have or haven’t done to transition, and no two trans people’s journeys are exactly alike.

We are visible everyday. Visibility won’t serve us though, there are a lot more things to make sure that we are safe than just recognizing our existence. Continue learning and unlearning!

And there’s no one way of being trans, that just forces the binary. Some trans people choose to medically transition, and some don’t. Some trans people choose to legally change their names or ID documents, and some don’t. Some trans people choose to change their appearance (like their clothing or hair), and some don’t. Likewise, some trans people may want to do many of those things but are unable to because they can’t afford it or for safety reasons. A trans person’s identity does not depend on what things they have or haven’t done to transition, and no two trans people’s journeys are exactly alike.